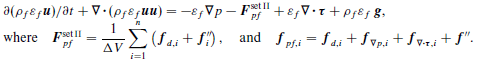

Particle statistics are extremely important for optimization of any industrial scale unit. Particle collision forces and stresses are difficult to quantify in traditional experiential techniques but is very valuable information because it allows Engineering prediction to be realized. For example, we may want a particular type of collision in flow problem. This can include favor over tangential to normal forces. It may not always be the desire to fully break a particle but instead “scrape” off material from composite particles made of soft and hard materials. Collision frequency is also a very valuable piece of information that can easily be realized from CFD-DEM simulations. Therefore making a Python code that does all these calculations is critical.

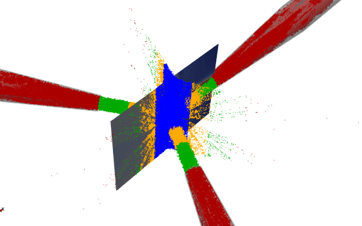

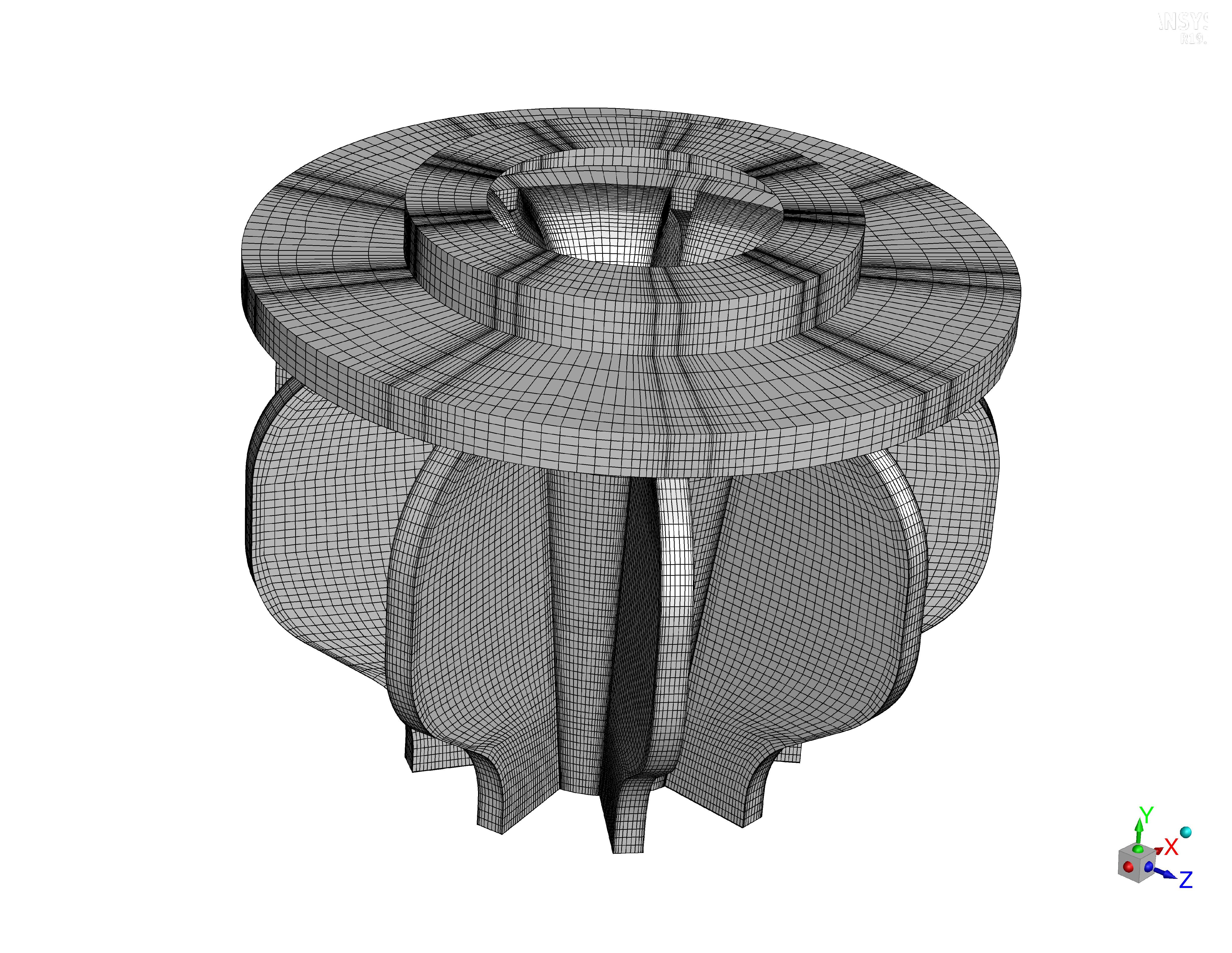

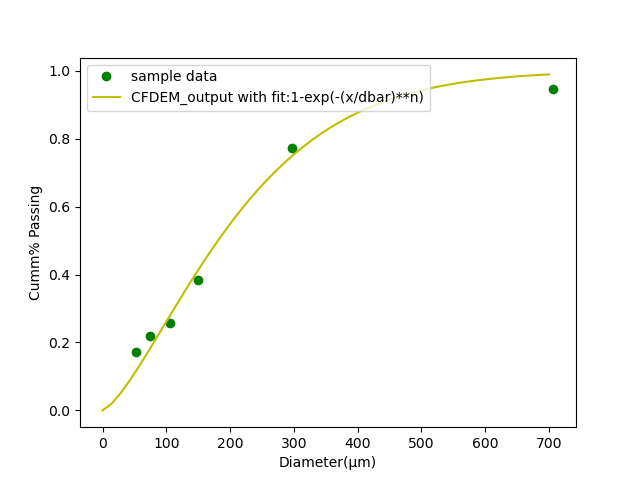

While making a code for outputs of particle statistics is relatively straight forward for simulations with a single particle size, what if we want a particle size distribution (PSD)? This is where filtering comes to view. We need to compartmentalize collisions between particle size fractions while also allowing something that us humans can interpret to further help optimization of the industrial unit. For example, shown in Figure1 is particle collision frequency of a simulation that I have previously performed for the company funding my research (DISA©). We then compare such information between simulations to determine which design we would like. For example, do we want a larger collision frequency of “like” sized particles or do we want more larger particles hitting the smaller ones?

We will want to know collision frequencies and particle collision statistics for force/stresses between all particle size fractions. I therefore created a code that does this in Python. I used Numba for speed and it also has the ability for filtering both by location and by value.

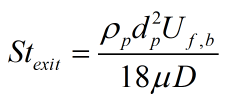

Starting at the simulation level the pairwise velocities, forces, and stresses are computed in the solver of LIGGGHTS© by the adding the following line to the simulation run script

compute frc all pair/gran/local pos vel id force_normal force_tangential contactArea

It should be noted that I have modified the LIGGGHTS© core code to output each particle radius during collision instead of the particle ID. I don’t need ID for my simulations and therefore this makes the most sense. This was easily done by modifying compute_pair_gran_local.cpp starting at line 412 to

if(idflag)

{

radi = atom->radius[i];

radj = atom->radius[j];

array[ipair][n++] = radi;

array[ipair][n++] = radj;

array[ipair][n++] = 0;

}

Now we output the particle radius during each collision, and this is used in our Python code.

The Python code starts by inputting all files into memory using the Glob Python package, setting as numpy arrays for contents of each filename, and finally concatenates all the files into a single large numpy array. Some initial calculations and arranging of the array are performed to make it more manageable. This is performed by a function I wrote.

file_list=glob.glob('dump_frc_*')

alldata=read_and_calc(numFiles,file_list)

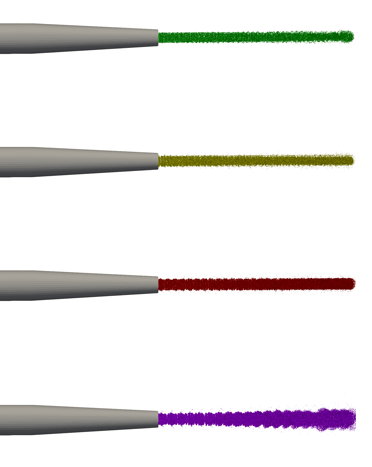

If wanted, this can then by filtered by location. For example, I am filtering out all the collisions occurring at center ,jetstream , nozzle exit, and inner nozzle areas in the follow code snippet.

centerData = custom_filter(alldata,cn_rxz,0,0.0254)

jetstreamData = custom_filter(alldata,cn_rxz,0.0254,0.0508)

nozExitData = custom_filter(alldata,cn_rxz,0.0508,0.0889)

innerNoz = custom_filter(alldata,cn_rxz,0.0889,0.4445)

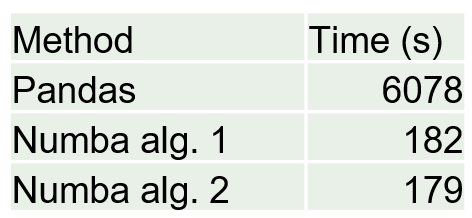

I talked about the custom_filter function in a previous post. This is the most computationally demanding portion of the code because I’m essentially going through each row one by one and filtering, for this case, all particle collision locations with a radius (about the origin) less than a specified value. I tried this before in Pandas and it was ridiculously expensive but now using Numba Python package it is very reasonable by approaching C++ or Fortran speeds.

@nb.jit(nopython=True)

def custom_filter(arr, columnNumber,min,max):

n, m = arr.shape

result = np.empty((n, m), dtype=arr.dtype)

k = 0

for i in range(n):

if arr[i, columnNumber] >= min:

if arr[i, columnNumber] < max:

result[k, :] = arr[i, :]

k += 1

return result[:k, :].copy()

I then collect all collisions in three-dimension Numpy Array with the first two elements of the array being the pairwise collision radius_i and radius_j, and then the third value being whatever value you want specified in that array. For example, it could be the velocity, the force, or the stress.

center_normStress_all = collect_all_collisions(centerData,particle_radii,cn_normStress)

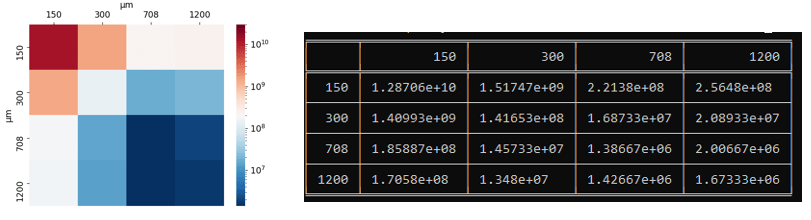

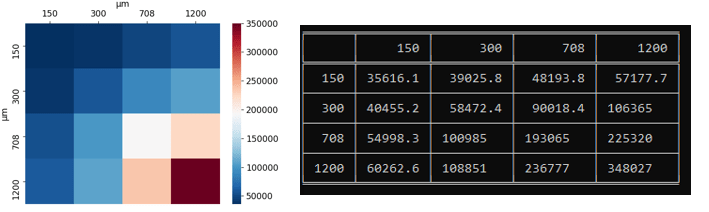

In this code snippet I am taking all collisions in the center region, passing the particle radii of the collisions (the uniques of the collision rows), and specifying that I want the normal stress of these collisions. This gives me the three-dimensional array for the collisions. I then created a function that returns all the statistics of the collisions.

nub_values,min_values,max_values,mean_values,var_values, skew_values,kurtosis_values = describe_all_collisions(center_normStress_all,particle_radii)

This returns 2-dimensional arrays with statistics, and I then print out the table and heatmap by

plot_heatmap(mean_values,uniques,filename = 'center__mean',plot_min = None, plot_max = 350000)

print(tabulate(mean_values, diameters, showindex=diameters, tablefmt="fancy_grid"))

This has proved to be a very valuable tool in my arsenal when analyzing these CFD-DEM simulations. This code will be uploaded to my GitHub if anyone is interested.